One Man’s Search for Everyman’s Piobaireachd

By Paul Ross

Australian piper Paul Ross of Newcastle, New South Wales, has contributed this lengthy piece on piobaireachd interpretation. We would be interested in what others make of his controversial monograph. Please respond by commenting in the usual way or email pipingpress@gmail.com

I have been a bagpipe player since I was 12 years old, over 50 yrs ago. In the course of that time I have had the good fortune to be mentored by piping eminents such as Donald Bain and Malcolm MacRae, and I have most notably mentored Greg Wilson whilst he was an Australian Defence Force Cadet in Canberra. No small thanks are due on my part to my original pibroch teacher, Mick Hagerty, a retired pipe major in the Cameron Highlanders , a native Gaelic speaker from South Uist, who right from the outset ‘grounded’ me in the integral relationship of pibroch music to Gaelic culture in the way he told the story, interpreted, sang and played the tunes he taught me. I had no trouble connecting with Mick’s teaching as my Gaelic singing maternal Granny, whose family were from Islay, had been a significant person in my formative years. By my late teens I knew that in order to further my knowledge, skill and understanding of pibroch I would need to live in Scotland.

I arrived there in early 1977 and contacted an old friend, Gordon Ferguson who had played in Muirheads in the 1960s. He had returned from Oz to the Black Isle. Gordon informed me that Malcolm McRae was married and lived nearby. I had not had contact with Malcolm for some years but was aware that he had become a pupil of Bob Brown. We three met for lunch. Malcolm offered to teach me and I accepted his offer. Within a short period I was a tenant on his property in Cannich ‘living my dream’ of living in the culture and learning the music. I stayed there for the next nine months.

In short order I realized that Malcolm was an informed and exacting teacher of pibroch. He viewed the music and practiced playing Bob Brown’s interpretation of the tunes with a precision which was impressive and competition winning. I worked hard, learned much and will always be grateful for the sharing of the knowledge about pibroch that he afforded me. However as the months passed my playing, though it may have been improving in technique, was becoming ever more constrained and joyless. I had not come to Scotland to spend all my time aspiring to play a perfect Bob Brown interpretation of a tune in a piping competition. Much to Malcolm’s chagrin I spent days in the Mitchell Library in Glasgow copying out, by hand, the complete Binneas Is Boreraig (out of print in 1977) and travelling to the Celtic cultural Festival in Lorient, where I met my future Scottish wife.

By the time I left Strathglass in early 1978 I had lived through a shinty season, occasionally playing pipes for their home games, seen the snow on the hills and the deer in the glen and met some great people including Jimmy McIntosh, Murray Henderson and especially Donald Bain with whom I established a friendship which endured until he died. All this as well as making some significant advances in my understanding and small advances in my own ability to play ‘good music’.

By mid-1979 I was back in Australia, in Canberra, with my Scottish wife, establishing my family and my career and playing my newly acquired set of Duncan MacDougall pipes with a superb Willie Sinclair chanter. (Another of my several trips out of the glen down to Willie’s workshop in Edinburgh; he made me a beauty). My time in Scotland had provided me with a gold seam of knowledge and experience to be mined. I did not feel the need to join a band and rarely played in competitions so I was and continue to be ‘under the radar’ of the orthodox piping scene here.

Through the 80’s and 90’s I had the good fortune to occasionally host, in my home, pipers whose music I admired. Jimmy McIntosh and Donald Bain, amongst others, visited. These brief encounters sustained and affirmed my personal piping journey.

One day, during the mid 80’s, Greg Wilson who had come to the Australian Defence Force Academy in Canberra visited my home and so began, what has become from my perspective, a most fortuitous and fruitful connection with both Greg and New Zealand piping. Since 2008, I have been a frequent visitor to the Hastings Games. You will have already gathered that I think that no individual no matter how brilliant has the ‘sum‘ of what pibroch is. Its study has been for many a lifetime’s work. However, when I reflect on my time spent in the company of Donald Bain, I find I am in accord with Donald’s view as I recall it. Donald thought that great music is composed out of significant human experience and should be played so that ordinary people hearing it should feel connected to, and even affirmed, by it. If it does not always fill the hearer with a sense of pleasure then it should at least strike a chord of appreciation in the human heart as to its beauty. If it fails to do either then in Donald’s view it is noise not music. I think Donald is right, especially about pibroch as it is played in our time. There is no debate that the bagpipe played well has the capacity to ‘touch the hearts’ of ordinary people from every culture. There is something almost primal in the way people respond to a live performance. However, I have often wondered if this has been the case with pibroch in much of the 20th century. Even though I am certain that it was never the intention of the individuals concerned, the effects of the great time and effort that has gone into its study by some of its greatest exponents appear to some to have had a ‘reducing’ impact. Pibroch, great music that it is, is generally spoken of in terms of schools of thinking and correct ways of interpreting it and playing it. Pibroch and pibroch competition has become the accepted gold standard for elite pipers, played to an ever increasing list of determinants best known and recognised by the judges. It is in today’s world a performance of music accessible and meaningful to a select few. It is no longer the great or big music of ordinary people. Most ordinary people would not have heard one, and few could connect with it. Having arrived at this realisation, I lost heart for a time and was not playing particularly well. I knew that the music was great; that hadn’t changed. So had we missed something vital, and if so what, and where, should I start looking? I did not have long to wait for my answer.

The New Zealand piping community is a very different scene to that in Australia. They do not have the same tyranny of distance that we do here, and they have a well established community of Scottish descent who continue to participate in fostering the culture. There is a vibrancy and currency about their activities which I find energizing. In 2011Dr Angus MacDonald was the visiting expert at the seminar run by the NZ Pibroch Society following the Hastings Games which I was privileged to attend. Dr Angus, as I recall it kicked off a general discussion on pibroch by saying ‘there are no rules’.

He got my attention straight away. I had in my possession excerpts of an interview you [Robert Wallace] did with Allan Macdonald which was published in the West Highland Free Press on 22 August, 1986. I asked Angus what his brother was getting at when he said that, ‘I do resent, to a certain extent, how it (i.e. music of Gaelic origin) has been taken over by certain elements who want to separate pibroch completely from the effects of language and traditional music…’. Angus’s response as I recall it was that in competitions the quality of the pipe and execution are the prime considerations and that any consideration of music runs a distant third if indeed it is considered at all. He asked me if he had answered my question. My response was that indeed he had!

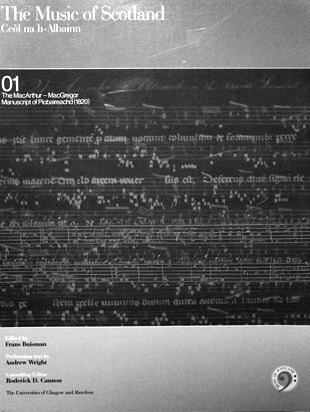

Angus is a masterful tutor. What really got my interest, apart from his superb playing, was a copy of the MacArthur-MacGregor Manuscript which he left on a coffee table for people to peruse. I subsequently obtained a copy of the manuscript and also the two volumes of Donald MacDonald along with the two volumes of Allan MacDonald’s ‘Moidart’ collection. All very well, but the challenge was how to turn the MacDonald/MacGregor tunes into music. I brought to my task the tools of my work life. I have PhD in economics and a degree in Chinese. These may suggest a capacity for intensity of focus and acuity for tonal sound. In addition, I have now been retired for a number of years so I had time to commit. I have approached the tunes in the same way I would approach a foreign language. Modern methods of effective language learning require ‘cultural immersion’. I proceeded on the basis that the tunes are a window into the heart and soul of Highland culture. They are without dispute a record rich with cultural meaning and understanding for our times, not something that can be casually visited and turned into something passable using the standard toolkit carried by pipers i.e. a good instrument, a dexterous set of fingers and a preference for a particular setting. This is serious music which requires serious attention.

Angus is a masterful tutor. What really got my interest, apart from his superb playing, was a copy of the MacArthur-MacGregor Manuscript which he left on a coffee table for people to peruse. I subsequently obtained a copy of the manuscript and also the two volumes of Donald MacDonald along with the two volumes of Allan MacDonald’s ‘Moidart’ collection. All very well, but the challenge was how to turn the MacDonald/MacGregor tunes into music. I brought to my task the tools of my work life. I have PhD in economics and a degree in Chinese. These may suggest a capacity for intensity of focus and acuity for tonal sound. In addition, I have now been retired for a number of years so I had time to commit. I have approached the tunes in the same way I would approach a foreign language. Modern methods of effective language learning require ‘cultural immersion’. I proceeded on the basis that the tunes are a window into the heart and soul of Highland culture. They are without dispute a record rich with cultural meaning and understanding for our times, not something that can be casually visited and turned into something passable using the standard toolkit carried by pipers i.e. a good instrument, a dexterous set of fingers and a preference for a particular setting. This is serious music which requires serious attention.

I began applying this approach two years ago. An integral aspect of the progress that I feel I have made has been the weekly critique/mentoring that has occurred throughout this time by my friend Graham Adams who spent two years living in Scotland being tutored by Bob Pitkeathly in the late 1960s. Graham has been a piper for over 50 years and is a serious pibroch enthusiast and player. He has given his time and knowledge freely and generously and is as enthused as I am by the potential of these manuscripts. I have finally found the music that I was looking for when I went to Scotland all that time ago. For anyone tackling these pibroch settings I would suggest the following:

I began applying this approach two years ago. An integral aspect of the progress that I feel I have made has been the weekly critique/mentoring that has occurred throughout this time by my friend Graham Adams who spent two years living in Scotland being tutored by Bob Pitkeathly in the late 1960s. Graham has been a piper for over 50 years and is a serious pibroch enthusiast and player. He has given his time and knowledge freely and generously and is as enthused as I am by the potential of these manuscripts. I have finally found the music that I was looking for when I went to Scotland all that time ago. For anyone tackling these pibroch settings I would suggest the following:

- You must have ability to turn a manuscript into music – this seems obvious, but for pipers who rely on copying the playing of others, it may be a skill they do not have, or are incapable of acquiring.

- If you are not a Gaelic speaker, treat the settings as a foreign language – if you have the Highland DNA, which I have on both sides of my family and have spent some time being immersed in the culture, it is a distinct advantage, as there is an implied familiarity with aspects of the culture. Once the language is learnt the message in the manuscripts is abundantly clear.

- Embrace the execution in total – no cherry picking such as sticking to the modern taorluath and crunluath without the ‘so-called’ redundant low A.

- Benchmark what you come up with against music that is unequivocally an integral a part of current culture so familiar to ordinary people that they don’t realise that they heard it at their granny’s knee and she heard it at hers.

The benchmark I use is a setting of Sine Bhan that was taught to me by a good friend and near neighbor Chris Duncan, an outstanding Scottish fiddle player and a long associate of Alasdair Fraser. When I can lead in to a ground playing Sine Bhan and there is a seamless transition and no discernible difference between the pieces of music then I know that I am in the ‘ballpark’. I also apply what I call the ‘car park’ test. If you go to YouTube and query ‘National Mod Dunoon 2012’ you will find the massed choirs in the car park singing a number of songs, including Sine Bhan. Whenever I start working on a tune now I try to visualise what the approach of the massed choirs might be.

In my view when the ceol mor and the singing at the Clan Donald Quaich are part of a seamless programme of Gaelic music then we will have arrived at a time and place of significance. A milestone in the reclamation of some lost aspects of our culture. A place where we will come to know and understand better who we are. And knowing better who we are and where we have come from we are better than ever positioned to choose where we are going to go and who we will become. Something mighty will have been achieved.

Do you agree? Let us have your views on this fascinating subject. Email pipingpress@gmail.com or leave a comment below.

I’ve noticed a well intended ethnocentrism in discussions of pibroch. Perhaps this effort to reclaim the Gaelic roots of pibroch has been around for centuries, I do not know. But in my recent explorations into old settings, manuscripts, books, and the implications they bring to pibroch performance, I’ve been led to folks who share their musical insights by reference to Gaelic song, harp and language.

On the one hand – I get it. Culture informs musicality (and vice versa).

On the other hand, one of the things I worry about is the possibility that this kind of effort may devolve to a standard of “authenticity” that is exclusive only to those of/in that culture.

Now, why does that bother me? Not because it means I may always be the outsider (having neither the experience nor the “DNA”). Rather, I worry about the ramifications of continuing to single out piobaireachd as something “other” in the musical landscape. It has been that status as “other”, as “strange”, that seems to cause us (as performers) to feel somewhat defensive about our love of it: we always feel this need to explain the music, conceding it’s oddity.

Well, I don’t find the music odd, at all. In the breadth and depth of musical history, theme and variation is ancient and universal. And pipes were the second instrument ever fashioned by humans (drums being the first).

While celebrating its origins, perhaps it’s time to assert our place in the greater musical pantheon and find ways of reaching out to other musicians and other audiences, lending them the wisdom of our wondrous instrument and music, while in turn revitalizing our tradition by allowing our musical cousins to rub off on us a bit.

I applaud Mr. Ross’ efforts, but suggest that what he is advocating is something that simply makes sense to me as a musician: to make this music truly special, it must be played MUSICALLY.

Accepting that such a concept as “musicality” may be culturally specific, it needn’t only be: good music is truly universal in some deep-seated and human way.