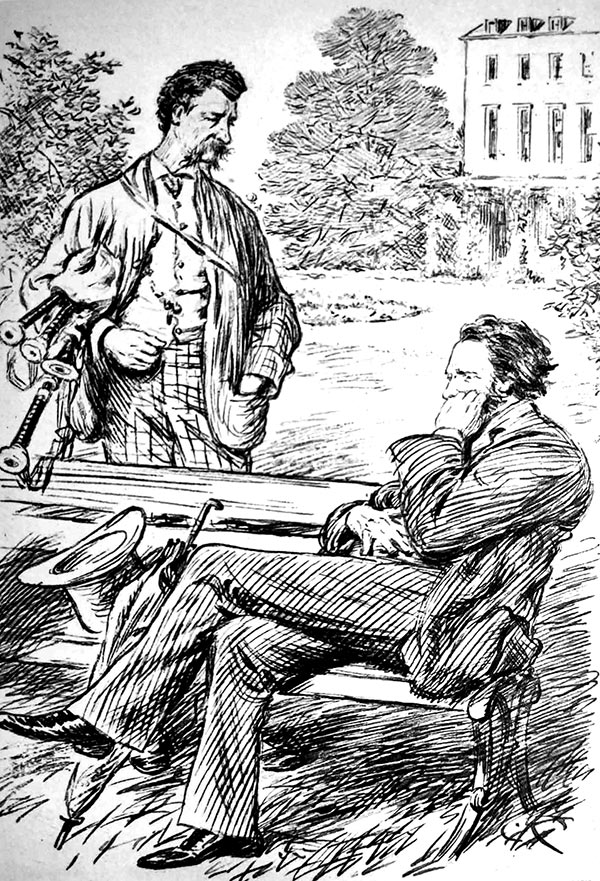

We continue with our illuminating article on Charles Keene, 1823 -1891 (above), the Victorian illustrator, piper and contributor to the satirical magazine ‘Punch’….

In George Somes Layard’s book ‘Life & Letters of Charles Keene of Punch’, Keene is asked ‘Have you mastered the practice stick? Glen in his ‘Complete Tutor for the Great Highland Bagpipe’ tells us the practice chanter is more difficult to blow from having no reservoir of air but is better adapted for playing in a room.

‘Glens, says Sir George Grove in his ‘Dictionary of Music’, are now chiefly noted for their bagpipes of which they are the recognised best makers (1879).’

Keene doesn’t answer the question directly but it is clear his enthusiasm for pipes is undimmed. Elsewhere he goes on, ‘I have just had the opportunity of getting a Breton bagpipe (Binion [sic]). It is coming from Brest made by one of its best artists. I fancy it has only one drone. I have asked for a book of the tunes they play but am doubtful if they have anything in that way.

By Francis Chamberlain

‘I heard from Glen lately that there was the prospect of some old MS pibrochs being published. I’ve lately learnt two fine ones, The Massacre of Glencoe and MacIntosh’s Lament. They are in [Angus] MacKay’s collection.

‘I want to send you the lament of the great Mr C____, the Beethoven of pipers.’ [No indication is given of who the composer Mr C____ is. General CS Thomason of ‘Ceol Mor’ fame?] ‘I’ve read of its being forbidden to be played in some campaigns for it made the Highlanders so miserable.’

In February 1884 Keene writes, ‘I find since the dentist has been at my mouth I cannot play comfortably with a stiff mouthpiece. I must go up to Edinburgh and consult Glen. A piece of flexible tube on the mouthpiece will put it right I fancy.’

The book: ‘It was in the ‘land o’ cakes’ [Scotland] that he could practice uninterruptedly to his heart’s content. In London this pursuit did not meet the appreciation he felt it was due.’

In another letter Keene writes, ‘I feel I am getting rusty with my big pipes though I work with the practice stick. I’m in hopes of getting up to the Highlands this year and then I’ll have a spell at them.

‘I met an amateur practising in Hyde Park [London] the other night about 11 o’ clock. I wish I had the cheek to do that.’

In 1885 Keene discovered a godson of his had turned out a ‘first rate piper’ and he ‘skirled away the best part of one Sunday’, remarking that the child had a ‘thorough Scotch mother and father!’ This gave him, as may be imagined, immense gratification.

Keene’s correspondence continues: ‘I have had a letter from an official of the Siamese legation….the King of Siam had bought two sets of bagpipes and wanted to know how his henchmen were to be taught and that little Glen had referred them to me!’ A dozen Siamese musicians subsequently travelled to London for an exhibition and played in the Albert Hall on their native instruments. Two of their number were instructed on the pipes by an Army piper from a Highland regiment and picked up the instrument ‘remarkably well’.

Keene again, ‘I’ve just been practising on my small pipes. I can only do this in a very makeshift fashion by converting a small Scotch chanter into a Northumberland one by plugging up the end! I’m waiting for a reed I ordered half a year ago of old Reid of North Shields who is a dilatory old boy, but picturesque, and his wife Holbein would have liked to paint!’

To a friend, ‘I hope you’ve made progress with the practice chanter. I dare say being used to the flute you have found it awkward stopping with the second joint of the fingers of the lower hand. But resolutely get over this. I should find out a piper and have a few initiatory lessons. Play slowly at first and lift the fingers high and bring ’em down like hammers…this I believe is the antique style.

‘When I began I made a dummy bagpipe chanter (with large holes) that I carried in my pocket and fingered on it on every possible occasion as I walked home at night etc…’

- To be continued.