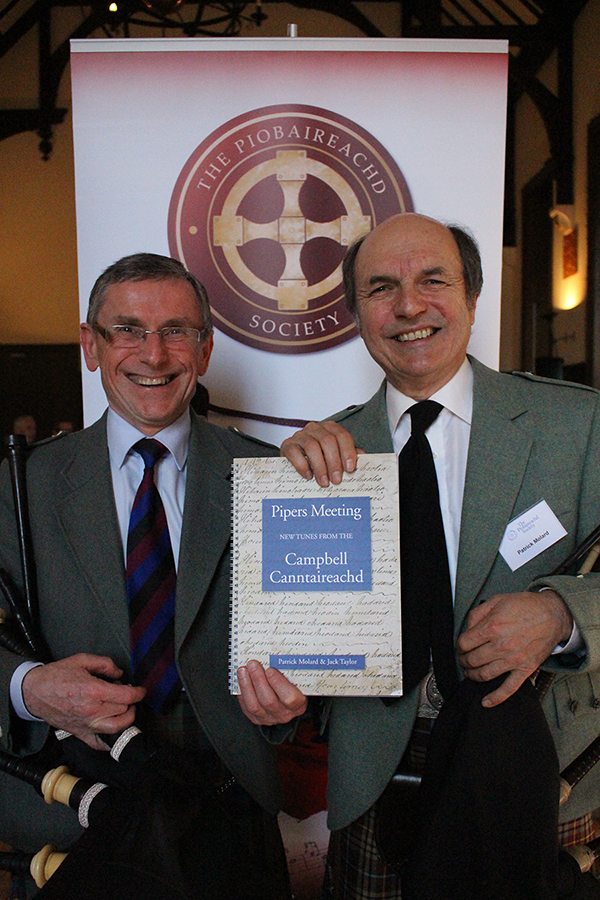

The launch of this book has had an impressive impact: inclusion in the Piobaireachd Society (PS) conference programme isn’t surprising, though nonetheless very welcome, but it was great to have significant coverage on the BBC’s ‘Pipeline’ programme.

The Campbell Canntaireachd manuscript (CC) is the oldest known collection of piobaireachd, written in vocables, a system for presenting the music in words (not in staff notation), reflecting the teaching of ceol mor by singing; the two volumes of the CC collection have long been a source of tunes and settings, for example in the PS collection.

The ‘Pipers Meeting’, by well-known piobaireachd experts Patrick Molard [pictured top] and Jack Taylor, contains 45 tunes from the CC that are not in current publications, many published in staff notation for the first time, including the eponymous ‘Pipers Meeting’. Patrick Molard has been working on CC for decades; he gave us a presentation of some of the relatively unknown CC tunes at the 2012 PS conference and this led to the collaboration with Jack Taylor that has brought us this fascinating book.

I am still getting to grips with it; this review gives my initial impressions and thoughts, one of which is that the wealth of material is almost overwhelming!There is a variety of tunes on offer, from short, simple pieces, to the massive Taviltich (you’ll play 238 taorluaths and 238 crunluaths in this tune if my arithmetic is correct!), with plenty in between, offering a breadth of music: attractive tunes, interesting tunes, unusual tunes, sometimes all three together!

The book is physically well presented, A4 size and geared for playing, having a ring binder format that sits open comfortably, hands free. The scores are clear, similar to PS style, but with some differences, notably that taorluaths and crunluaths are not routinely marked with T & C. This and other features suggest the book is not an obvious text for piobaireachd beginners, but, given the subject matter, it’s perhaps reasonable to assume the book is more likely to appeal to seasoned campaigners.

There are no time signatures, reflecting one of the key differences of the CC from other original sources, but tunes are barred and in lines (lines are also given in the CC), so, effectively, most tunes have the time signature demonstrated. Phrase structure is not always clear from the CC and, where the authors believe it appropriate, tunes are presented with unusual phrase structures, without aiming for standardisation of pulses or bars per phrase and avoiding the emending that, for example, General Thomason might have undertaken.

[wds id=”2″]

The book is upfront about where cadences have been added and it’s good to have these and other changes numbered and flagged on the scores, so one can identify straightforwardly where they are in each tune. Also good to see reference to where tunes have appeared previously, e.g. in Angus MacKay’s MS. The CC form of crunluath a mach on D is explained and used.

Some comments now about specific tunes to illustrate aspects of the book (again not in any way attempting comprehensive analysis): There are tunes with only one or two movements, conventional ‘full’ tunes (i.e. having taorluath and crunluath variations, though some of these are also quite short), some very long tunes, including MacDonald’s Gathering, which is a form of tune I think only found in the CC (see also PS Bk 15 ‘Ken so Lurrich’), with a frankly excessive number of very similar variations – here there are six crunluath variations! There are several tunes with the enigmatic CC title ‘One of the Cragich’, including one with crunluath movements in the urlar in phrases that are redolent of Joseph MacDonald’s more elaborate ‘cuttings’.

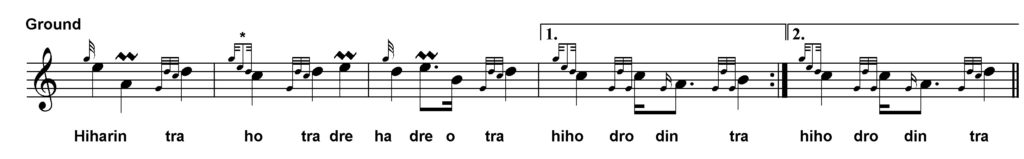

Not all the tunes in the book will catch on, but I would expect most piobaireachd players to find some that appeal and there is certainly plenty of food for thought, with material that cries out for further research by enthusiasts. Amongst the tunes that may not get many full outings, several have interesting individual variations that are worth a look, e.g. Variation 2 of Hiharin him tra.

There are short attractive tunes with only one or two variations, e.g. Volume 1 Tune 35 (V1: T35) only urlar and ‘thumb’, V1: T28 only urlar and two variations, and also short tunes with very simple later variations, which seem abbreviated compared with the urlar and early variations, e.g. V1: T52. One point discussed at the PS conference was whether it might sometimes be appropriate to elaborate the later variations in such tunes rather than feel the need to stick to what is in the CC? We have tunes from other sources that have had variations added or embellished after the time when the CC was written and there is evidence that Angus MacKay did develop and add variations to some tunes (see notes PS Bk 3 Lament for Colin Roy MacKenzie). Of direct relevance here is V1:T53 (Hindo rodin hindo rodin in CC, The Comely tune in Angus MacKay), which stops at the tripling in the CC, but Angus MacKay has a whole suite including crunluath a mach.

In contrast, Fuinachair in Angus Mackay’s MS, has fewer variations than appear in same tune in CC (V1: T27, ‘Pioparich aon Croch’). There is strong evidence that Angus MacKay had access to the CC, though possibly not the CC volumes that are extant today (see PS Bk 5, p129 notes for Sobieski’s Salute). As far as I am aware, we remain uncertain whether CC scores that Angus MacKay saw were the same as those we have today nor indeed which tunes he took from the CC and which he collected from elsewhere and are now coincidentally in the CC as the only other extant source. (I’m happy to be corrected on that.)

Included in Pipers Meeting is The Duke of Perth’s March (V2: T58), which Angus MacKay has as The Duke of Perth’s Lament. Although most of the tune is identical, Angus MacKay has a rather more elaborate setting, very attractive, with a definite flavour of Lament for the Son of King Aro; did Angus Mackay produce this setting of the tune or did he collect it from another source? Oddly, neither has a crunluath a mach, despite 28 of the 32 crunluaths being on notes B, C & D.

V1:T53, mentioned above, illustrates another point of interest: when I have used the CC previously, I have found some vocables difficult to decipher. Is it ‘i’ or ‘e’, as in ‘dari’ or ‘dare’, is a frequent dilemma. V1: T53 line 2, bar 3, and where similar recurs, appears to have ‘dari’ in the CC and Angus MacKay, but ‘bari’ in ‘Pipers Meeting’, whereas in the next bar Angus MacKay has ‘dari’, while the CC and ‘Pipers Meeting’ have ‘dare’. This is likely to be an example of where the many hours Patrick has spent reading the CC helps to figure out what is going on.

Not every score is wholly lucid, but the exceptions emphasise the high standard of the book overall. V1: T37 shows a single F gracenote, which is an unusual note in any form of pipe music including piobaireachd, and there is no annotation or explanation, which led me to suspect the misplacing of a gracenote something that can be very easily done with music writing software. However scrutiny of the original shows the note F. My impression would be that the CC is giving F as a note, rather than gracenote – I don’t know if this occurs elsewhere in the CC, but, as above, I would bow to Patrick’s experience in reading it. He must have acquired substantial extra insight from its extensive study.

The Pipers Meeting appears to have few misprints but there is a lack of clarity about starting point for repeated sections, e.g. in Taviltich. I have used the CC over the years to explore apparent anomalies in tunes, e.g. the inconsistencies in MacSwan of Roaig, but I had not myself ventured to explore unknown tunes in it. One should not underestimate the massive task that has been undertaken to produce staff notation scores for these tunes from canntaireachd, it has been a major undertaking.

The authors have been at pains to point out that the settings presented are their interpretations and they do not claim them to be authoritative. Given potential difficulties posed by the CC, especially the lack of information regarding timing of notes, I think it would be sensible for most of us to follow the lead we are given here – though we are at liberty to bring our own ideas into play if we feel so inspired!

There are some elements that might be worth addressing if a second edition follows or if some form of ‘Sidelights’ to the CC is produced. It would be particularly interesting to learn more about meaning of tune titles. Also, not much is said about the CC itself and for those not familiar with it the book provides little explanation. So it might be helpful to point readers towards sources of further information, for example the PS website, where a scanned copy of the canntaireachd can be viewed. Presumably, though, the purpose of this book was to present tunes for playing, rather than offer an analysis of the CC or indeed of the tunes themselves. In this it has succeeded. I have had no difficulty finding half a dozen tunes that I am keen to learn. If you are a piobaireachd enthusiast, you should look at this book. A big thank you to Patrick and Jack. I anticipate many more happy hours poring over it.

• John Frater is a distinguished amateur piper. He is a member of the Piobaireachd Society’s Music Committee and a winner of the leading amateur piobaireachd prize, the Archie Kenneth Quaich, and also the Royal Scottish Pipers Society member’s championship on many occasions.

[wds id=”10″]

Recent Comments