My father was an expert on pipes. If he had been a bagpipe maker I bet he would have produced the Stradivarius bagpipe. He had the ear, the sound, and the technique for working with chanters.

If he took a wee bit out of the top of a hole then he would mix up some glue and shellac and fill in the bottom to balance things up. That way he kept the same diameter on the hole and the correct sound. He would also use this mixture to flatten a note but then would compensate by taking something out of the bottom of the hole so as to keep the volume the same. Now that’s all very well if you have the time to do it, but you should really take something out of the bottom of a hole if you’ve taped the top. Mind you chanters are very expensive so it may be as well to make do with losing a little of the volume.

My father would build up a hole to flatten a note and then have to take it off again if the next reed wasn’t suitable. There was no tape in those days. The first chap to use it was Captain John MacLellan. I remember being at Inverness and we were talking about chanters. John was always over talking to me and asking if he could try his chanter next to mine. He noticed mine was all built up with something and he said ‘oh, we just use tape’. That was a gift from heaven! But don’t forget that in those days reeds seemed to be more consistent.

John MacDougall Gillies used to see my father in his shop in Renfrew Street and he would hand over some reeds saying. 'Take these, your boys will need them.’ We didn't seem to have the problems with reeds then because they we re a bit lower pitched. They didn't need the work you need today. Today I could have tape on every hole of my chanter trying to get the best sound I could. Chanters are definitely higher pitched. Listen to the top hands and especially the low Gs. Terrible! I remember judging at Inverness recently [late 1990s]. I won't mention any names.

There were three of us judging and this particular person played with a low G that sounded like a low A. I just washed my hands of it because it was discordant. After the performance I said to one of my fellow judges 'that was a shame about the low G’. 'Oh, what was wrong?', he said. I said it was terrible; but he hadn’t noticed it. There are an awful lot of bad low Gs nowadays. The scale isn't consistent. Even the boys who come here for lessons I say to them 'that low G's flat or sharp' and they haven't realised itI wouldn't advise poking and cutting a chanter mind you unless over a period of time I had reeds from different makers and the chanter was consistently off on a particular note; then I would know it was time for the knife.

As far as reeds go the first thing to remember is that it has not got to be a hernia snapper as the Americans call them. It has got to blow freely with a good ‘crow’. If it has got that then you' re half way there. Reeds are different now. They're too strong unless you' re fortunate and you get a weaker one. If you can blow a reed without drones when you first put it in then it is okay. Do that every day for a week. Then you should be able to start one drone and gradually build up your sound.

My father would blow the reed in rather than cut it in; he didn't like doing too much of thaT. As I said earlier there's no pleasure without pain. A reed that is blown in is something you can depend on throughout the summer. I don’t worry too much about how a reed looks, whether it is well made or not.

It is the sound that matters. I made my own reeds and I worked at them myself. I assumed everyone knew what to do with reeds. I just taught myself by trial and error. I made my own tools, my own chisels. Once when I was working down in Exmouth I was living in the Atlantic Hotel. We would be thinking about going north for a holiday so I would get the pipes going so that I could have a go at the competitions.

I couldn't play in the hotel. It was a very private establishment and the people were pretty well off. We lived in the top flat; best view in Devon. Anyway I built a small sound proof chamber. Gwen and I had to creep in at the dead of night with big sheets of sound proofing material about 3/4 inch thick. It was a kind of sweat box but we got it fixed up and it allowed me to blow. As usual I'd chucked the pipes and hadn't been blowing and I couldn't keep the drones going. I thought there was a hole in the bag. The chanter reed was the weakest thing I could find. It was a sort of tinny thing. That was all I could blow. It took me from early June until Cowal [held in late August] that year to get the three drones going but I think I was successful.

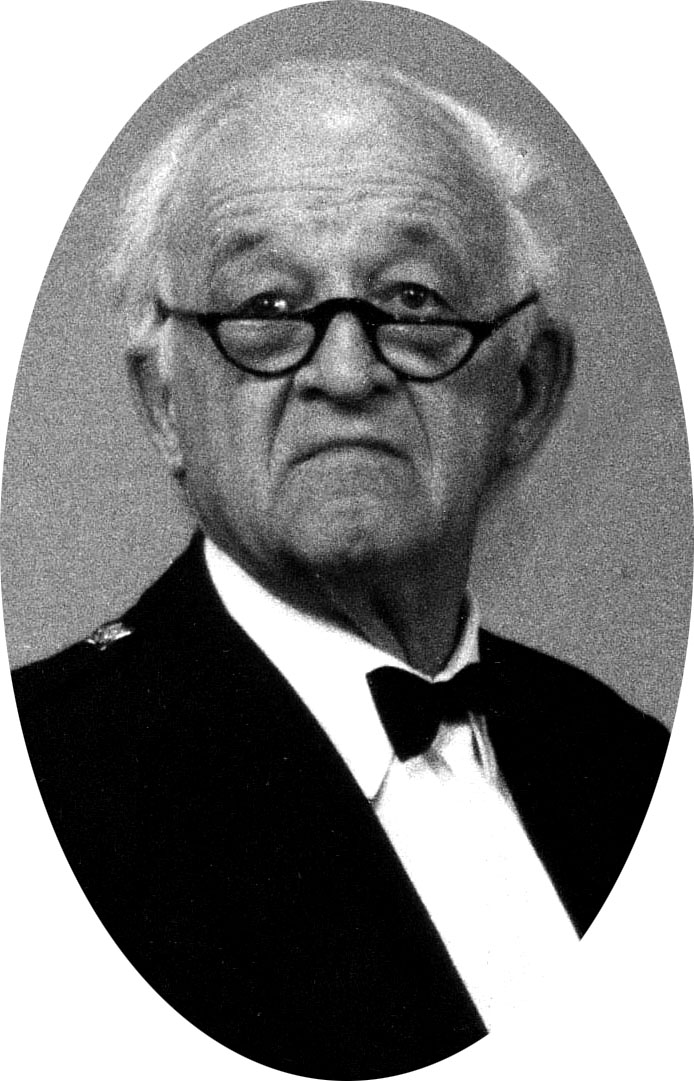

James Campbell, Kilberry, records this tribute in the sleeve notes to Donald's CD recording on the Suibhal label: 'On a Friday evening in December 1947 I took the overnight train from London to Glasgow. The official purpose of my journey was to transact some Piobaireachd Society business in connection with the printing of the K.ilberry Book. But this business was no doubt timed to coincide with the pibroch competition which the Scottish Pipers' Association was due to hold on the Saturday. At any rate, that Saturday afternoon found me in the Highlanders' Institute with a programme containing a number of familiar names and also the unfamiliar names of some who had grown to maturity in the recent war years.

James Campbell, Kilberry, records this tribute in the sleeve notes to Donald's CD recording on the Suibhal label: 'On a Friday evening in December 1947 I took the overnight train from London to Glasgow. The official purpose of my journey was to transact some Piobaireachd Society business in connection with the printing of the K.ilberry Book. But this business was no doubt timed to coincide with the pibroch competition which the Scottish Pipers' Association was due to hold on the Saturday. At any rate, that Saturday afternoon found me in the Highlanders' Institute with a programme containing a number of familiar names and also the unfamiliar names of some who had grown to maturity in the recent war years.

The judges were Willie Ross and George MacDonald, Dunoon. At the end of the day the prizelist was mostly composed of pre-war competitors. Robert Reid (Praise of Marion) was first, John MacDonald, Glasgow Police (Lament for Patrick Og) was second, Archie MacNab (Lament for Mary MacLeod) was fourth, Nicol McCallum (Prince's Salute) fifth. The third prize winner was a newcomer, one Donald MacPherson, whose playing of the canntaireachd setting of the Battle of Auldearn left an abiding impression on me.

This impression I duly reported to my father who relayed it to Willie Ross, receiving reply to the effect that they 'might well have put him first' So there was Donald with his foot on the ladder, and his subsequent ascent was rapid. At Oban the following September he won both the Gold Medal and the Senior Piobaireachd competitions on the same day - the Gold Medal (Old Men of the Shells) in the morning and the Senior Piobaireachd (Queen Anne's Lament) in the evening. And two years later at Inverness he was placed first in the Clasp competition with the formidable Nameless tune, Cherede darievea. These successes hoisted him to the top of the competitive tree where, with some intermittent spells of 'Iay off' he remained for forty years.

His record speaks for itself, but there were two features about his playing which for the record are worth emphasising. The first was his sureness of touch and feeling for the music. This is an innate quality which can not be described or defined and which I do not believe to be capable of being passed on to others by teaching. The other was his mastery of his instrument. This is something that can be learnt, given the necessary sensitivity of ear, and which in Donald's case is surely traceable to the ministrations of his father, who was a perfectionist in this respect.

I remember lain MacPherson telling me that he was always insistent on his sons tuning their own pipes from the word go. Whatever temptation there was (and it could be severe) to take charge and however discordant were the sounds of ill-tuned drones in a confined space, the only assistance forthcoming from father was a slight manual indication of 'up' and 'down'.

The competition period ended in the early 1990s. Donald then followed other distinguished contemporaries - Bob Brown, John MacFadyen, John MacLellan, Donald MacLeod - in a further career as judge and teacher, though these contemporaries were unfortunately not afforded the longevity which in che case of Donald MacPherson we are thankful to be celebrating in 2003.'

• To be continued. Enjoying this series?, then please support our advertisers and the ppresshop! Meanwhile here is a sample (below) from the 'Living Legend' CD. Buy it here.