James Campbell As I Knew Him

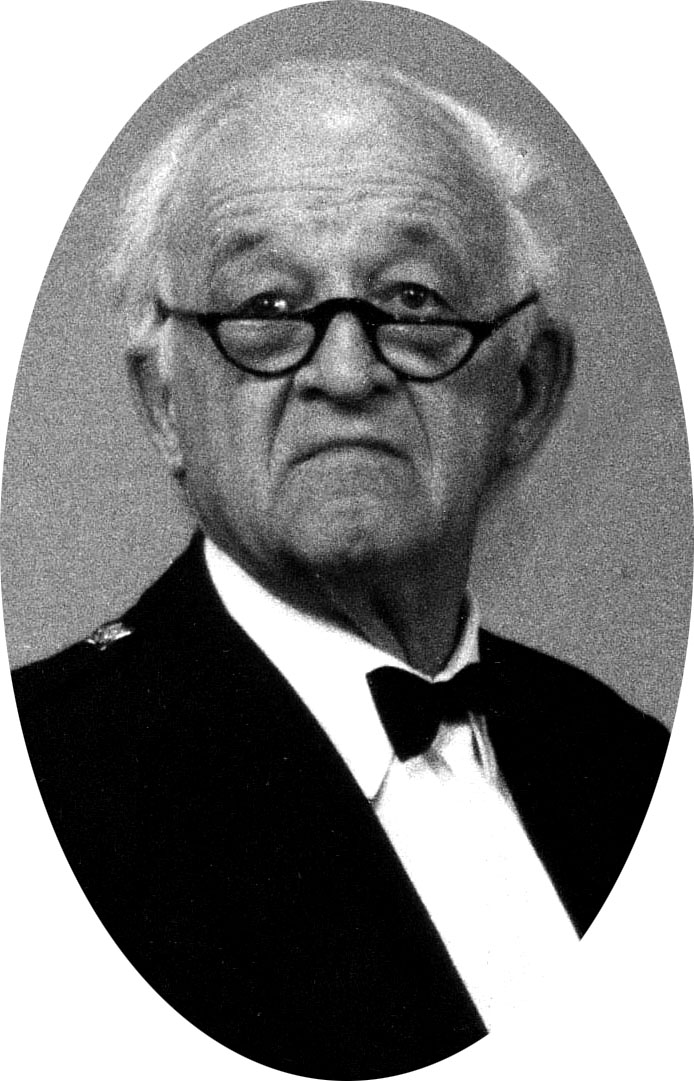

This is the first excerpt from the lecture given by Jonathan Gillespie at the Birnam Hotel, Perthshire, last March. In it he tells of his relationship with one of the main figures in 20th century piobaireachd, James Campbell of Kilberry. The lecture is organised annually by the College of Piping. We are grateful to Mr Gillespie (pictured) for his kind permission to reproduce it here.

I must establish from the outset that I am neither an ‘authority’ on James Campbell nor will I pretend to be one this evening. I am merely someone who had the great fortune to be taught by James and through that process to come to count him as a friend. Others whom James taught would be just as qualified as me to speak – no doubt Roddy Livingstone, Pat Terry, Neil Mulvie, or Neil Esselmont would have other perspectives to bring and anecdotes to relate, as would others who had the privilege of knowing James for a lot longer than I.

I must establish from the outset that I am neither an ‘authority’ on James Campbell nor will I pretend to be one this evening. I am merely someone who had the great fortune to be taught by James and through that process to come to count him as a friend. Others whom James taught would be just as qualified as me to speak – no doubt Roddy Livingstone, Pat Terry, Neil Mulvie, or Neil Esselmont would have other perspectives to bring and anecdotes to relate, as would others who had the privilege of knowing James for a lot longer than I.

As for me, I owe James a great debt, both in the friendship he showed to me as well as his guidance and encouragement of my piobaireachd playing, and it is for that reason that I am pleased to be here to speak about him this evening. I have decided to structure my text around a tribute I wrote for the Piping Times shortly after James’ passing in December 2003 into which I shall weave others’ words as well as James’ own. In particular I have drawn on obituaries published in the Piping Times and in the national press; on text from the programme of a celebration of James’ life held at Pembroke College, Cambridge, in June 2004 at which I was invited to play; and on James’ own words from an interview conducted by Dr John MacAskill in The Voice magazine published in early 2000. I shall also quote from personal letters from James to me. But I must from the outset establish that I have relied heavily on other sources, not least James himself, in order to speak authoritatively about him, so I claim little of what follows as my original work. I have also tried to focus exclusively on James and his work rather than on his father.

So let us begin with some biographical detail: James, his two brothers and twin sister were born into the Indian Civil Service. Their mother, Violet Beadon (who died in 1949), was the younger daughter of the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, and their father Archibald (1877-1963), Puisne judge in the High Court at Lahore, needs no introduction in piping circles. In his own time James was to add to his father’s seminal work two Side Lights to the Kilberry Book, although he confessed his greatest pride to be ‘The Elusive Appoggiatura’, a contribution of his to the Piping Times of June 1988.

James had no memory of India as the family returned home in 1917, the year after his birth, when his father had accumulated a year’s leave. At the end of that year, Archibald returned to India whilst James and his siblings spent most of the next ten years under the eye of their grandmother and other indulgent relations in England. Their parents came home at regular intervals, but it was not until his father retired in 1927 that James remembered any sort of family home.

James went to prep school at Seaford House in Littlehampton, Sussex, by coincidence very close to Lancing College where I have been Head Master for the last eight years. James followed in his father’s and brother’s footsteps to Harrow School, and then followed them again to Pembroke College, Cambridge, to read law.

Of his introduction to piping James (right) said that he was taught the scale and gracenotes at a quite early age but had no zest for the music until he was about 15. A small class was held at Harrow taken by P/M David Taylor, formerly of the Scots Guards and trained by Willie Ross, who was then in charge of piping at the Royal Caledonian School, a few miles away in Bushey. As a result of a prod from his Housemaster, James joined this class. According to James the Housemaster knew nothing about piping but was well disposed to it and wisely spotted that it was a field in which James could compete successfully with a more precocious younger brother. So it was by dint of that spur of encouragement that he made a start. James admitted to having been quite a bolshie teenager (times may change but teenagers, I suspect, do not!) and that any pressure from home on the subject of piping would probably have soured him for life. Fortunately his father had the great wisdom to appreciate this and his forbearance, plus the acumen of the Harrow Housemaster and the skilled tuition of P/M Taylor, set him off on the right track and fired his enthusiasm.

Of his introduction to piping James (right) said that he was taught the scale and gracenotes at a quite early age but had no zest for the music until he was about 15. A small class was held at Harrow taken by P/M David Taylor, formerly of the Scots Guards and trained by Willie Ross, who was then in charge of piping at the Royal Caledonian School, a few miles away in Bushey. As a result of a prod from his Housemaster, James joined this class. According to James the Housemaster knew nothing about piping but was well disposed to it and wisely spotted that it was a field in which James could compete successfully with a more precocious younger brother. So it was by dint of that spur of encouragement that he made a start. James admitted to having been quite a bolshie teenager (times may change but teenagers, I suspect, do not!) and that any pressure from home on the subject of piping would probably have soured him for life. Fortunately his father had the great wisdom to appreciate this and his forbearance, plus the acumen of the Harrow Housemaster and the skilled tuition of P/M Taylor, set him off on the right track and fired his enthusiasm.

Undoubtedly James’ exposure to piobaireachd as he grew up influenced him. James admitted that even as a child one subconsciously absorbs the sound of piobaireachd playing, however uninteresting and unmusical it may seem at the time. This unconscious absorption, he maintained, stands you in good stead when the time for pleasurable application comes. And if that time never comes, an early and unwilling familiarity with the sound of the music is liable to leave its mark. He related that his sister endured the sounds and conversations of four besotted male pipers in the family, plus those of similarly infected visitors to the house, and though she had since never voluntarily attended a piping function, she could put the name to many of the tunes when caught off her guard!

Sticking initially to ceol beag, it was in 1935 in Edinburgh, as he was about to go up to Cambridge, that he heard two piobaireachd which set him off and thereafter it was ceol mor all the way. We will return in a short while to this moment in James’ life. Within a couple of years he was judging for the Piobaireachd Society, on whose Music Committee he would serve for the following forty years, latterly also as Honorary President.

In 1939 at Stirling Castle James joined the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, as a subaltern in the Territorial 8th Battalion, 154th Infantry Brigade. They were in the British Expeditionary Force to France, narrowly escaping through Le Havre in June 1940, when the rest of the 51st Division were taken prisoner. In the hasty retreat James, one of the fortunate few to get away, lost a valuable set of pipes. The 8th Argylls regrouped into the 78th Division, arrived in North Africa in November 1942, saw action notably at Tebourba Gap (in December 1942) and at Longstop Hill (in April 1943), where in an afternoon dash through heavy machine-gun fire they captured the Western ridge. Landing in Sicily in late July 1943 they were in on the 78th Division’s long haul up the length of Italy, past Cassino-Two, to the woods along the Senio behind Florence, and then on to the breakthrough at Argenta Gap (in April 1945). James’ calm in the gruelling business was an inspiration to a shell-shocked junior officer. He was twice wounded and awarded the Military Cross after Monte Spaduro (in November 1944). The citation for the award of the Military Cross reads:

‘Captain Campbell, as Officer Commanding Headquarters Company, has always been given, when the Battalion is in action, the responsibility of supervising the maintenance of the forward troops. [This period] has been one when the difficulties of administration have demanded the very utmost of those whose lot it fell to. The areas where the Battalion was in action, and the approaches to them, were constantly under enemy mortar and shellfire, especially directed to harass the lines of maintenance. Supplies had to be brought by mule at night over miles of track often knee deep in mud, sometimes over uncharted ground from which the mines had still to be cleared. Night after night Captain Campbell led the mule train up; when shelling had reduced it to complete disorder, as very often happened, the utmost drive, tenacity, and courage were needed to restore control. Captain Campbell showed all these qualities and more. His gallant example and complete disregard for his own safety when shelling was at its worst were entirely responsible for the consistent regularity with which the supplies came up. His bravery and conduct under stress has always been of the highest order and worthy of the greatest praise. Captain Campbell, who has served with this battalion throughout the North African, Sicilian and Italian Campaign, has commanded Headquarters Company since October 1943. During the whole of this long and difficult period he has at all times shown the greatest bravery, energy, and devotion to duty.’

And now – at last, I hear you say! – to our first tune of the evening. Let me take you back almost eighty years – to Edinburgh in 1935 – when, having left Harrow and just before going up to Cambridge, we are told that James heard two piobaireachd which set him off on his lifetime’s journey with our great music. Those tunes were Lament for Sir James MacDonald of the Isles played by the great Willie Ross and Lament for Mary MacLeod. It is the latter will shall hear this evening, chosen by me as a memory of James’ teaching of this tune, in particular ensuring the correct emphasis of the hiharin (on the low A, of course, rather than the introductory E) and the timing of the ground and the first variation. I recall my pride at having been identified as a pupil of James’ in one of my early competitive appearances playing for the Dunvegan Medal in the late 1980s, this from my timing of the ground and in particular the hiharin (of which more later) which was subsequently featured briefly in an episode of Pipeline. Now that I look back with the wisdom of hindsight I can say that this recognition amply makes up for the inadequacy of the judging in not placing me on that occasion! In 1935 the piper who inspired James Campbell was Lewis Beaton; this evening it is Euan MacCrimmon.

James Campbell – lawyer and Cambridge Don, and man of Argyll

At Cambridge James had taken first classes in the Law Tripos and read for the Bar. De-mobbed in 1946 he became a tenant at 1 Brick Court. The head of chambers, Colin Duncan KC, was a libel specialist, and there James was said to have been his industrious devil. On occasion the famous Duncan’s mastery of his brief was memorably confounded by his junior’s more precise knowledge of the law. It is said, however, that, practising on the Oxford Circuit, James earned more by playing bridge in the Bar mess than from the dock briefs available at Quarter Sessions. He continued at the bar until his feline skill in cross-examination was frustrated by the infantry-man’s wartime legacy of hard-hearing. In 1952 he became Director of Studies in Law at Pembroke, his Cambridge College, and the teaching of its undergraduates became the focus of his activity.

James taught Roman law, contract and tort, and particularly the law of evidence. We are told that it was teaching exemplary in accuracy, style and pitch; not coaching or question-spotting. To pupils of every kind – through a rare combination of kid-glove discipline and no-nonsense acumen about strengths and weaknesses – he was altogether special. Years after their graduation he had instant recall of them, zest to know their doings and those of their friends, their children, wives and former wives. Those whom he taught or tutored, or whose sports he turned out to watch in even the foulest weather, felt they had been looked after with superb efficiency; and in return gave lifelong affection.

One of his former pupils, a Lord Justice, wrote in The Times (the London Times, that is!) in December 2003 of James’ uncanny ability to dispense a wee snifter or nightcap of gin and not a lot of tonic in a half-pint tankard. He was the one don known to everyone in the college. No matter how inclement the weather, James would be on the touchline or on the towpath to smile at our incompetence or to rejoice in our success. He never forgot us.

James’ memory was prodigious, developed from his prep school where he learnt the batting and bowling averages of generations of English cricketers. When a lawyers’ dinner was arranged to mark James’ retirement in 1984 they had to turn to James for help as only he could remember the undergraduates (and most of their wives and children – and their dogs) and place them in their right years.

Another former pupil who played a part in arranging a dinner given in honour of James’ 80th birthday recalls the Old Hall in Lincoln’s Inn being filled with “his” lawyers, the top table comprising one Lord Chief Justice, two Lords of Appeal, and countless High Court and other judges and QCs. James requested no speeches but allowed his toast to be proposed shortly, after which he spoke for 40 minutes without a note, keeping the assembled company in thrall with tales of his life and times. The account concludes: we adored him.

To be continued