Twenty five years ago Professor Dan MacInnes gave the annual John MacFadyen Memorial Lecture. His subject was piping in Nova Scotia and the wider Canadian Maritimes.

The winters were so severe for the first settlers, said the professor, that hardly a bagpipe survived. They literally cracked up – no doubt along with some of the early adventurers.

By Robert Wallace

They had never experience the biting bitterness of the ‘big ice’ before. To make it through to spring they had to have some sort of entertainment and when they eventually graduated away from ther early shelters the immigrants resorted to singing and floor dancing mostly in the kitchen, the warmest part of the house.

Piobaireachd had crossed the Atlantic with Donald Rory MacCrimmon in 1783. It died out – as did most other piping. There were few playable instruments left and even less teachers.

A trickle of immigrant pipers kept things hanging by a thread. Somehow piping scraped by and gradually ‘community pipers’ became prevalent in the frontier villages.

When Seumas MacNeill arrived at the region’s Gaelic College in the late 1950s there were certainly pipers, but the standard of fingering was, to him, shockingly poor and he set about doing what he could to correct things.

Most of the pipers were folk musicians who played tunes adapted for this kitchen dancing and from the fiddle tradition. The rhythms were exciting, blind ear to the crossing noises, and still are.

More recently revisionists have seen this Nova Scotian piping as a lost Scottish tradition forgetting that piping never died out in the source islands of the Uists and Barra. It had crossed the sea and altered as most things do 3,000 miles from home in a completely different environment.

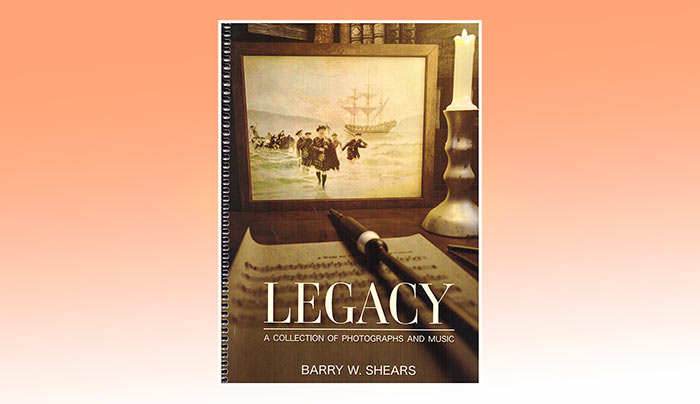

In his recent book, ‘Legacy: A Collection of Photographs and Music’, Barry Shears pays a wonderful tribute to this uniquely Canadian piping development.

He has gathered 115 photograhs together and laced them with an lucid, succint text. His book is spiral bound in 224 pages. The type is clear and the scores easy to sight read.

There are 192 tunes: 19 slow airs, 58 marches, 19 strathspeys, 49 reels, six hornpipes, 40 jigs, and one piobaireachd. New and old, some tunes appealed to me immediately and others did not. There are dozens of Barry’s own tunes too.

But this is more than just a tune book. It is a significant work of folklore gathering for which the author deserves all credit.

He has scoured and researched and recorded a musical tradition embracing Gaelic song, fiddle music and ancient pipe tune scraps and adaptations. He pays pictorial and literary homage to the leading lights.

The author knows his subject. The book is weighty and repays study. It is worth having.

- ‘Legacy: A Collection of Photographs and Music’ by Barry Shears costs $44.95Cdn plus P&P. To obtain a copy go to the author’s website here.